In the summer of 2007, Elizabeth Hardin-Burrola, a freelance writer based in Gallup, New Mexico, suspected that the local Catholic bishop wasn’t telling the truth. The Diocese of Gallup, a hardscrabble town on Route 66 that sits on the edge of the Navajo Nation, had announced that Bishop Donald E. Pelotte had to be flown to Phoenix after injuries sustained in a fall down the stairs. But Hardin-Burrola talked to the ER physician who attended to Pelotte and had called local police because he suspected the bishop was the victim of a beating.

The Diocese denied anything nefarious had happened. But in multiple pieces for the tiny Gallups Independent (daily circulation: 13,500), Hardin-Burrola eventually uncovered gruesome photos of Pelotte with severe bruises and black eyes that strongly suggested the bishop had in fact been beaten. The Gallup diocese had long drawn controversy for accepting priests suspected of pedophilia over the decades, and would go on to declare bankruptcy in 2013. However, the subsequent furor over Pelotte’s injuries led to his resignation less than a year after Hardin-Burrola’s first article appeared.

Every time her articles appeared online, Hardin-Burrola emailed a link to Abuse Tracker, a blog that has served as the most powerful platform for aggregating stories about sexual violence in the church and beyond. Tips poured in every time, from people across the country.

“I do believe that during the crazy last years of Pelotte’s tenure as bishop,” she says, “all my stories that appeared in the Abuse Tracker helped bring the attention of the Church hierarchy to the very dysfunctional Gallup Diocese…and helped them to push Pelotte to resign.”

Originally launched by the Poynter Institute in 2002, Abuse Tracker’s creator, Bill Mitchell—whose wife is a Church sex-abuse survivor—originally sought to keep track of all the articles emerging in the wake of the Globe’s series on the Boston Archdiocese, as newspapers across the country ramped up reporting on cases in their local parishes. A sidebar linked to the archives of other newspapers and a roundup of web sources devoted to helping survivors of sexual abuse.

Mitchell initially did the aggregation on his own, but the project quickly became, he says, a “Whac-a-Mole thing.”

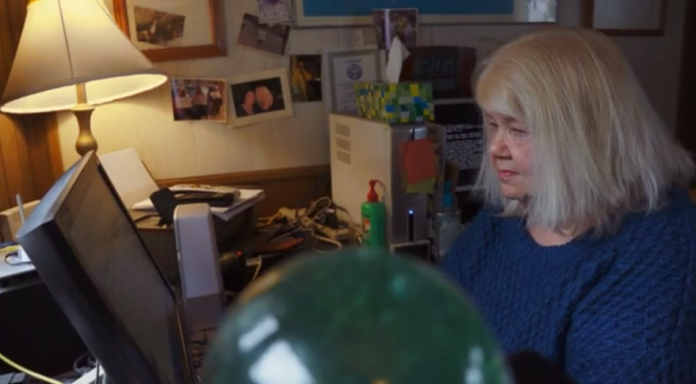

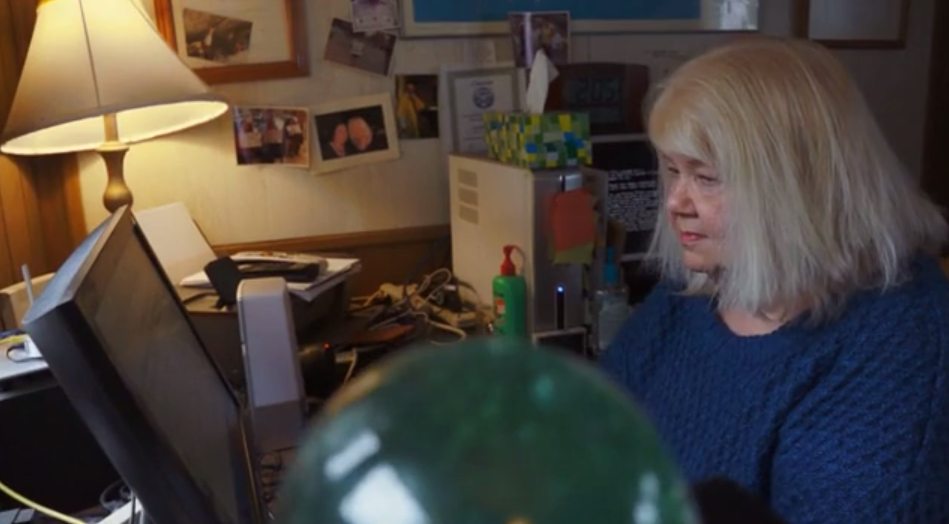

He put out a call for volunteers for Tracker, and found a few. Soon, its most prolific contributor was Kathy Shaw, a former religion reporter for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette, in central Massachusetts. Within a year, she became Tracker’s sole blogger.

Every day, the cradle Catholic posted dozens of stories—an excerpt, then a link to the full article—from publications across the world. She offered no commentary, no pictures—just aggregation. But the sheer number of stories Shaw posted daily (from 30 to 60 a day, 365 days a year) made Tracker a crucial resource, both for abuse survivors looking to connect with each other across the country and journalists like Hardin-Burrola who wanted their stories viewed by as many people interested in the scandal as possible.

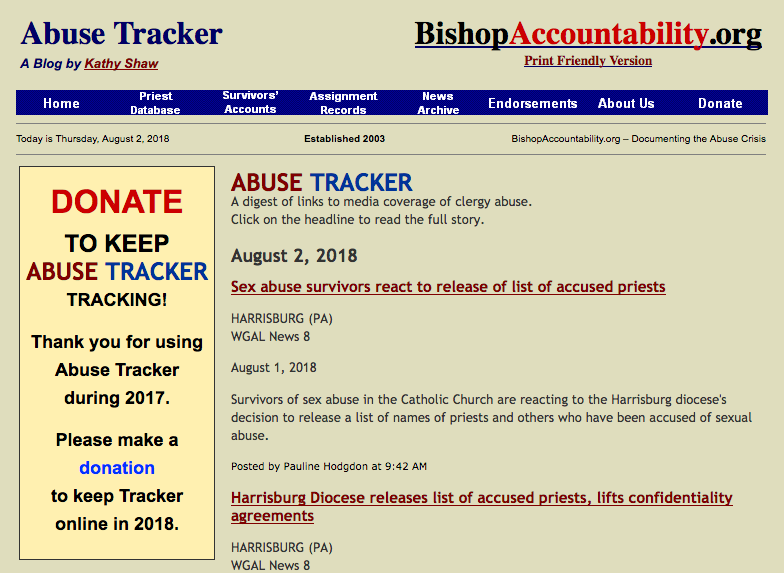

In 2006, Tracker was taken over by BishopAccountability.org, a Massachussetts-based nonprofit whose namesake website serves as an online repository of church documents and newspaper articles. Its mission is to “expose bishops who have abused children or vulnerable adults, or have aided abusers.”

Terence McKiernan, the organization’s president, had been a Tracker follower for years. “It’s the doorway into all of these articles that are necessary for the work that we do,” he says.

Shaw’s aggregation allowed McKiernan to compile names and connect the dots between different scandals across the United States to compile full assignment histories for pedophile priests. And she also let the group become aware of coverage beyond the United States by posting articles from Italian and Spanish-language newspapers. Tracker offered articles about a sex-abuse scandal in Chile that recently had Pope Francis issue an apology to survivors years before the American press covered the issue.

McKiernan described himself not as Shaw’s editor but as a “host”—they’d meet for a yearly seafood dinner, and exchange emails and calls every once in a while, but she was always self-directed. “I didn’t want to be on top of her, because this was her gig.”

In June, Shaw died, at the age of 72, leaving Abuse Tracker without its veteran. Sex-abuse survivors always treated her like a rock star at the yearly conference of Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priest (SNAP); at this year’s gathering in Chicago, those present gave her a standing ovation when a Powerpoint remembrance of her flashed on opening night.

“Sometimes, I’ve stayed on the phone and perused [BishopAccountability] alongside a newly disclosed [sex-abuse],” says SNAP volunteer Esther Hatfield Miller. “I then tell them, ‘This compilation list is the detailed handiwork of Kathy Shaw.’ The victim replies, ‘Thank her for me; I wasn’t sure I’d ever see [their abuser’s] name in a listing like this!”

Abuse Tracker will continue. To get by without Shaw, McKiernan has begun waking up at six to tackle the morning shift; taking over most of the posting for the rest of the day is Pauline Hodgdon, who started with BishopAccountability as an intern in 2010 and is now a projects coordinator and analyst.

She admires Shaw’s output—“I don’t think we will ever have one single person who could match her,” the 27-year-old says—and aims to put up at least 20 stories a day. Visitors to the site find that it’s still pegged as “A Blog by Kathy Shaw.”

But Hodgson has pushed Abuse Tracker in a new direction, covering subjects outside the Church, from Larry Nassar to Harvey Weinstein. “We’re getting more and more stories in the secular world,” McKiernan says. “We love covering those. The church people have a valid point to make that this is not simply a Catholic phenomenon” (Catholic League president Bill Donahue once called Tracker an anti-Catholic “inside job” for its “almost total fixation” on Catholic clergy).

Hodgson—who cites her Jewish faith as “another reason I think I bring different eyes to the work and to Tracker”—believes that young people outside the Catholic Church will find value in its latest iteration because they are “more willing to read these stories about institutional sexual abuse” than older people are. “I think my generation realizes that the more these types of stories are read, and spoken about, the harder it is for perpetrators to hide it,” she says. “Open dialogue is necessary to shift change, and we can’t have open dialogue if we do not stay informed by reading others stories of their experiences, and promoting their voices.”

To bring the blog forward in the era of #MeToo and social media, McKiernan is sending out a reader survey that will ask readers what they like about Tracker, and whether they’d like to see any upgrades, like original reporting or editorials. A daily roundup newsletter is definitely in the works. BishopAccountability is also about to undergo a website redesign, but McKiernan wants the look of Abuse Tracker (it retains the look of an early aughts Blogger page, a two-tone mass of text with no photos or multimedia whatsoever) to stay roughly the same, both to honor its history and so readers can get the “hubbub and mix” of articles that always made it “a constant reminder” of how widespread the crisis became.

“Tracker is still going to be going 10 years from now,” McKiernan says. “It represents the multifarious nature of this tragedy. If only Kathy were here to preside over those changes. We feel a responsibility to do it well because she did it so well, and we want to carry that on.”