On top of a bluff in San Clemente, the former mansion known as Casa Romantica stands as history, metaphor and a mirage.

An Andalusian arch frames the front entrance. Whitewashed stucco walls and Spanish-style red tile roofing surround a resplendent courtyard that played host to concerts, movie nights and wedding receptions in better times. A back terrace offers a picturesque view of the San Clemente Pier, a sought-after backdrop for newlyweds. To enjoy its splendor amid a pandemic, a sign advises guests to wear a facemask, sanitize their hands, and keep six feet apart.

Casa Romantica is the lodestone of San Clemente, the landmark that embodies the South Orange County city’s grandiose sense of self. By law, its first residents lived in homes similarly fashioned in its Spanish Revival style, the architectural genre that imagined a California where Mexicans didn’t exist but their fiestas and señoritas did.

By practice, San Clemente continues to think of itself as this City Different: far away from the rest of a changing OC, separated by Camp Pendleton from the rest of San Diego County. A seafront paradise unto itself.

This unflinching artifice was the dream of Ole Hanson, San Clemente’s city father, who called the Avenida Granada estate his home for several years.

He arrived to San Clemente in 1925 after teaming with a financier named Hamilton Cotton, who acquired thousands of acres of beachfront property once known as Rancho Boca de la Playa, to create the first of OC’s many master-planned communities. It was to be a career zenith for Hanson, who had gained nationwide acclaim in 1919 after crushing a general strike in Seattle while mayor of the city. He rode patriotism to prominence as “America’s Mayor” long before Rudy Giuliani played the part.

Seizing the moment, Hanson resigned from office and gave speeches across the country railing against Bolshevism (the antifa of the day) before imagining San Clemente as his gift to the United States that he proclaimed to love so much.

“I vision a place where people can live together more pleasantly than any other place in America,” Hanson once wrote a friend. “I am going to build a beautiful city on the ocean where the whole city will be a park; the architecture will be of one type, and the houses will be located on sites where nearly everyone will have his view preserved forever.”

He advertised San Clemente to the world by the name the city still wraps its self around: The Spanish Village by the Sea.

Hanson had no shortage of doubters. Naysayers thought it too remote to amount to anything. But his ambitious persona persists in the city as a point of pride, from everyday residents chugging a beer at Ole’s Tavern in downtown to history buffs that host reenactments of his first sales pitch to buyers.

The old-timers widely hail Hanson as a Shangri-La sage and fondly recall his battles in Seattle as an anti-Left model. Hanson’s hectorings echoes President Donald Trump’s current browbeating of socialists — real and imagined — on the campaign trail.

Yet Hanson’s record is more complicated than what his cheerleaders proclaim.

A century after his stump speeches about saving Seattle, the city remains a reliable outpost of Left politics and unionism. Socialist Kshama Sawant is the new firebrand on the city council and is serving a third straight term. Living wages and payroll tax hikes on corporations like Amazon are the lay of the land. Trump now blasts the city Hanson left behind as an “anarchist jurisdiction” overrun by radicals.

The same San Clementians who hail his reactionary politics conveniently ignore his work during the 1918 influenza, when he made the bold decision to close schools, churches and theaters to stem the spread. Hanson followed with a stay-at-home order for nonessential workers, banned large gatherings and made masks mandatory to board street cars.

In the midst of another pandemic, Hanson’s response seems impossible today for a man of his political ilk. He even met the impromptu Armistice Day celebration on Seattle’s streets with measured patriotism by reminding all of the merits of masks.

But with the Great War over that November and no more influenza deaths reported, Hanson’s America First mentality got the best of him, just like the current OC Board of Supervisors who rushed to open county beaches for Memorial Day this summer.

Back then, Hanson greeted a group of businessmen ahead of the holiday season with glee.

“Bust her wide open, boys!” newspapers quoted Hanson as saying. “Have the time of your lives! And at 12 o’clock tonight, when you have just started to celebrate, you have the joyful assurance that the ‘flu’ ban is no more!”

Another deadly wave of infection awaited in winter, just as it did in Orange County this summer. And just like medical experts predict will happen in the coming months.

Born on Jan. 6, 1874, Ole Hanson called the small, southern Wisconsin town of Union Grove home for much of his early life. The son of Norwegian immigrants became a lawyer before finding his passion as a traveling salesman. Hanson married and started a family when he decided to move to Seattle in 1902, the endpoint of a doctor-defying odyssey to recover from partial paralysis when injured in a train wreck two years before.

He quickly discovered a knack for real estate in the Pacific Northwest. Six years later, Hanson won election to the Washington State Legislature, where he championed an anti-racetrack gambling bill and supported an eight-hour workday for women and miners.

In 1914, Hanson ran for U.S. Senate on the Progressive Party ticket, Theodore Roosevelt’s short-lived experiment in Republican populism, but finished third. He fared better in the 1918 Seattle mayoral elections. The Seattle Star, then a labor-friendly newspaper, branded opponent James Bradford as the Industrial Workers of the World’s favored man in the race even though the “Wobblies,” as the radical union was popularly known, never endorsed any candidates for office on principle.

“Your ballot cast for Ole Hanson, will not be found side by side with a vote of an I.W.W., a pro-German or any other enemy of your country,” read the front-page endorsement. “Americanism is the issue next Tuesday. Seattle must and will register itself overwhelmingly American.”

In the wake of a world war and the Bolshevik Revolution, Americanism preached a patriotic cooperation between classes — so long as industrialists led the way. Any whiff of people-powered labor, as embodied by the Wobblies, became synonymous with sedition in concert with America’s foreign enemies.

Hanson bested Bradford by 4,600 votes — no slim margin, but far from a walloping.

His tenure began humdrum enough, save for the controversial closures during 1918 pandemic. But another, much more dramatic shut down loomed in Seattle’s near future — and it began at the docs, not with a virus.

With the First World War finally over, unions representing shipyard workers demanded raises above wartime wages. The workers — 35,000 strong — walked out in January 1919. Soon after, they appealed to the Central Labor Council for help. The council, representing 110 locals, delivered unanimous support for a general strike. A sense of utopian euphoria swept over Seattle’s socialists, famously summed up by labor journalist Anna Louise Strong’s editorial stating that “no one knows where” the strike will lead.

Hanson believed Strong’s ambiguity to be a bluff, based on a supposed Secret Service report that went like this:

A shadowy meeting took place on Oct. 22, 1918 in Linnton, a Portland neighborhood. Presided over by a Soviet agent from Russia, a group of fifty men from all over the nation convened. By the meeting’s end, all resolved to overthrow the government. The conspiracy would begin in Seattle’s shipyards, followed by a general strike.

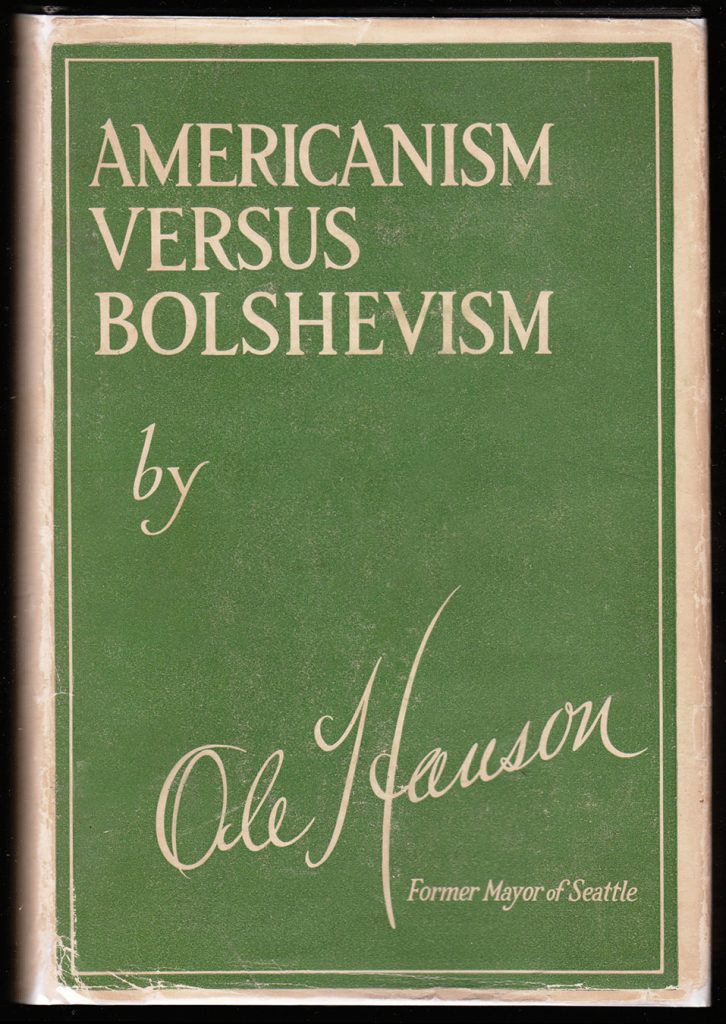

The account that Hanson offered in Americanism Versus Bolshevism, his polemic tome penned after the strike, is dubious at best. For the mayor, all leftist variants congealed into one subversive whole. The press echoed Hanson’s paranoia; the Seattle Star asked “Under Which Flag?” in a front-page headline on the eve of the general strike. On Feb. 6, he positioned himself as the last line of defense against a Bolshevik revolution in America when workers shut down Seattle.

Hanson issued a proclamation the following morning. “The time has come for every person in Seattle to show his Americanism,” he wrote. “Go about your daily duties without fear. The anarchists in this community shall not rule its affairs.”

The proclamation appeared on the front page of the Seattle Star — now anti-labor — alongside his ultimatum to the Executive Strike Committee that called for their surrender; under police protection, 100,000 copies of the newspaper blanketed Seattle later that day, while the feds shut down the labor-run Seattle Union Record.

“I knew, then, that the attempted revolution was crushed,” Hanson later boasted in Americanism Versus Bolshevism.

The mayor gave his police chief “shoot to kill orders” for anyone causing a riot. He had federal troops on standby. But the general strike, starting off 65,000 workers strong, remained a nonviolent affair.

Still, the American Federation of Labor’s tepid conservatism put intense pressure on the council to call it off. The effort hemorrhaged under the weight of all the forces against it; the strike ended just a week later, on February 11.

Thomas Murphine, Hanson’s friend and appointee as Seattle’s Superintendent of Public Utilities, ran the first street car through the city in triumph.

Hanson became a hero in a nation scared of anything that reeked of Red. Adulation from newspapers across the country elevated his profile. “Seattle’s Mayor a Champion of Order and Always Willing to Battle for it,” read the Feb. 9 Sunday edition of the New York Times.

Hanson had become the man the nation clamored for.

In April 1919, a curious package addressed to “Hon. Ole Hanson, Mayor, Seattle, Wash.” arrived to City Hall by mail. A secretary turned it upside down, spilling sulfuric acid from a loosely capped bottle bomb onto the floor. Hanson, away in Pueblo, Colorado, blamed labor for the attempt on his life and offered more bravado during a stop on his Victory Loan tour, a final effort to raise funds for the war.

“They know, also, that I never go about the streets armed,” he said as quoted in the San Francisco Chronicle. “But if one of them was to attack me, I would choke them to death with these naked hands.”

The tour took Hanson through several cities on the East Coast and catapulted him into national fame. A presidential buzz even surrounded Seattle’s “fighting mayor.” Back home, the Spokesman Review deemed Hanson “one of the best advertised men in America” second only to President Woodrow Wilson.

In Seattle, his political footing seemed as firm as ever. A month after the general strike, unions suffered a political coup in its wake. Three “law and order” candidates backed by Hanson bested a trio of labor-backed opponents during the Mar. 5 Seattle city council elections. They joined the mayor on the dais, but not for long.

During a special Aug. 28 council meeting, Hanson suddenly resigned, citing exhaustion as well as a desire to finish a book he had started. The 47-year-old, whose crop of red hair had turned grey, also looked forward to a little leisure. “I am tired out and am going fishing,” said Hanson in his resignation letter. “I have no political plans for the future.”

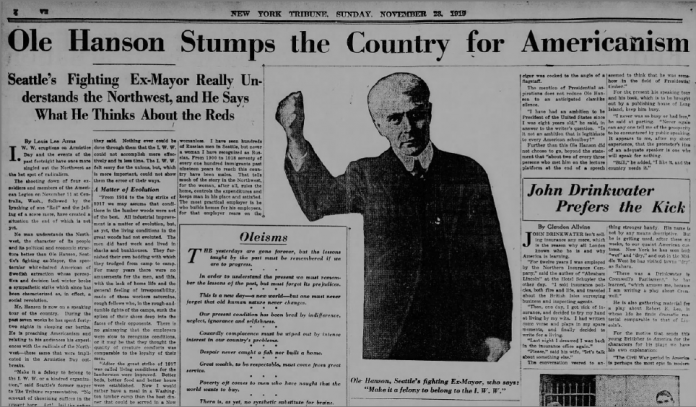

But Hanson continued touring the nation, preaching the perils of Bolshevism while putting the finishing touches on his book. A full-page story in the New-York Tribune showed the former mayor, fist clenched in triumph beneath a headline proclaiming, “Ole Hanson Stumps the Country for Americanism.” He had spent the last seven weeks on the road.

By the time the flattering portrait published on Nov. 23, 1919, Hanson continued tough-talking the Wobblies, telling the reporter that just being a member should be a felony. He blamed them as chief conspirators of the general strike, framing the stoppage as nothing less than a plot to establish the United Soviet States of America.

Although mum on presidential aspirations when he resigned, Hanson fielded a question in the Tribune piece about his political future.

“I have had an ambition to be President of the United States since I was eight years old,” he said. “Is it not an ambition that is legitimate to every American school boy?”

Yet Hanson stayed away from the fray of the Republican primaries in 1920. He had a book to sell, one that prolonged his folk hero status as America’s mayor but delivered him to San Clemente, not the White House, as hoped.

Americanism Versus Bolshevism read very much like the last hurrah of his political fame. Hanson could only muster five chapters in delivering his account of Seattle’s short-lived general strike. The rest of the book offered a less compelling, mish-mashed take on Bolshevism in Europe, where he toured after his American barnstorm.

Upon returning home, Hanson railed against the Red threat of European immigration despite his own roots. But the act wore thin. Fifteen months of speaking engagements dried up.

Back in Seattle, the city council approved a grand jury investigation into Hanson’s negotiated purchase of street car lines while mayor. The probe revealed in 1921 that the $15 million price tag, passed by voters in Nov. 1918, allowed a utilities conglomerate to make nearly three times as much profit from the sale as it should’ve. Union newspapers pounced on the scandal, denouncing Hanson as a charlatan who beat his chest against the general strike to divert attention from a dirty deal.

“He managed to get advertised by the press of the nation as the hero of the hour,” reported Labor World, a newspaper in Minnesota. “He then proceeded to capitalize this publicity by resigning as mayor and signing a speaking contract which he admitted under oath had brought him several thousands of dollars each month.”

Hanson had somehow squandered much of that wealth by then, rebounding from debt only by acquiring oil interests from the Mexican government. He escaped the streetcar scandal with a mild slap that accused him of “slack business methods” in having countered the conglomerate’s initial lease offer with a bloated purchase price.

But his political career was over.

Hanson moved to Los Angeles with a national stature already too shriveled to be scathed. He returned to real estate, and developed a tract along Slauson Avenue in Spanish Revival style while still looking for land to build an entire beachside community in such a fashion.

The idea first stirred Hanson’s imagination during an earlier visit to Southern California when a stretch of coastland caught his eye along the way from San Diego to Los Angeles. It offered him the chance to create a community, not govern one. Financier Hamilton Cotton led a consortium that acquired the land destined to become San Clemente.

Hanson yearned to transform it into his long sought-after Spanish village.

Avenida del Mar, the heart of San Clemente, remained mired in mud on Dec. 6, 1925, when Hanson pitched a sales tent and hoped for the best. A month earlier, Hanson and Cotton publicly announced development plans for the five-mile stretch of beachfront property equidistant between Los Angeles and San Diego.

Hanson waited patiently for buyers to arrive and claim a piece of his dream.

An ad in the Santa Ana Register the day before announced the reservation sale. “San Clemente has perpetual race restrictions,” it declared, “and every house, be it a two-room loafing place or a mansion, must be of Spanish design.”

Cars started slowly arriving after 11 a.m. By noon, according to author Homer Banks’ recollection in The Story of San Clemente, The Spanish Village, Hanson welcomed hundreds with a fried chicken luncheon and a speech. Only, the fiery orator of old turned dull, delivering his vision for San Clemente as “coldly as an accountant” according to Banks. With lots available between $500 and $700, he found enthusiastic buyers all the same. The Los Angeles Times had described the developer’s idea as “unusual” but by day’s end, Hanson counted $125,000 in property sales to the surprise of many.

The city steeped itself in romanticized notions of “Old Spain,” taking its name from an island visible off the coast christened in the early 17th century by Spanish colonizer Sebastian Vizcaino in honor of Saint Clement of Rome, the fourth pope of the Catholic Church. In Hanson’s Spanish “fantasy heritage” ideal, a term first coined by writer Carey McWilliams, all whitewashed buildings would be affixed with red tile roofs. None would obstruct the other’s view of the Pacific Ocean. Everyone who signed purchase clauses agreed to as much.

“I have always wanted a seaside place for myself and my family,” Hanson told the Los Angeles Times. “It will be a clean environment where there will be…no shacks, just a decent place for the family to enjoy the ocean in beauty, comfort and happiness.”

With such a promise, San Clemente continued to defy the doubters.

By 1927, Hanson’s real estate company relocated to the city. He commissioned architect Carl Lindbom to build his mansion overlooking the ocean. From Casa Romantica, Hanson admitted to a Los Angeles Record reporter in 1928 that owning a city was much more fun than governing one. With $8 million in land sales since the first lots were made available, it was more profitable, too. Hanson enjoyed a new reputation in Southern California as a real estate genius.

“I’ve been out of politics for three years now,” he told the Los Angeles Record. “I’m through with vote getting.”

San Clemente incorporated the following year. The first municipal elections happened in 1929. Murphine, a fellow Seattle strike buster who followed Hanson to serve as a tract manager in San Clemente, became mayor.

All seemed tranquil enough as Hanson’s storied life had reached the edge of the Western world.

“The Pacific Coast is the terminal station of the age-old journey of the white race who have now spanned the globe,” Hanson boasted in The Story of San Clemente. “This westward urge is as deep seated as life itself.”

And then came the Great Depression.

By the end of the Roaring Twenties, San Clemente enjoyed a beach club, a new school, a hospital and improved roads. More than 1,400 residents called Hanson’s Spanish village home and kept tabs on their town’s explosive growth through El Heraldo de San Clemente, the city’s local newspaper. Hanson commissioned Banks to pen The Story of San Clemente, the Spanish Village but the city’s fantasy heritage façade began to crumble in the wake of its publication.

The first fissures emerged at city hall in 1933 when Hanson declared political war on Murphine, an episode that escapes Hanson hagiographies.

Mayor Murphine blasted San Clemente’s city father as being behind a recall effort against him and two other councilmen. The San Clemente Businessmen’s Association accused the council majority of malfeasance, incompetence and abuse of power in seeking their removal. Murphine begged to differ; the real motive was failing to bow before Hanson’s every whim, criticizing his newfound foe for acting like San Clemente’s czar since its founding.

In one cited instance, Murphine defied Hanson’s “supreme power” by refusing to sack the city supervisor who hounded him for $40,000 in long-promised but never-delivered tract improvements. That October, San Clemente’s nascent electorate delivered the recall a stunning defeat. Murphine and Councilman Oliver T. Robertson retained their seats; only Earl Von Bonhorst lost his, by all of one vote. A furious Hanson convened a meeting at Casa Romantica, where the businessmen’s association voted to call for the OC district attorney to investigate the election. Von Bonhorst challenged Hanson to run against him in a special election, a race he won against another opponent.

San Clemente’s political turmoil didn’t end there.

Murphine resigned as mayor in early 1934, less than a year after an earthquake collapsed his bluff-top estate. Hanson didn’t take too kindly to A.T. Smith, who took Murphine’s place. He lambasted the mayor and council during a picnic for allowing the state government to build a shack on its beachfront property that failed to conform to the city’s Spanish-fantasy aesthetic. Smith called Hanson a “communist,” rushed the stage and punched him. Hanson fought back before the brawl turned political with an empty recall threat.

But both Hanson and San Clemente’s troubles transcended politics. Before the fistfight, the federal government sued Hanson and his company for $84,000 in taxes owed over the years, including $24,000 alone in 1925. A decade after the city’s founding, Bank of America came to own 40 percent of its properties, including Casa Romantica.

Dorothy Fuller, a longtime San Clemente resident, told the Los Angeles Times in 1991 about how her father, acting as a Bank of America vice president, oversaw the foreclosure of Hanson’s Casa Romantica. “Ole Hanson cried, and my dad could not hold back the tears after Ole broke down,” she said. “It was especially difficult for my dad because he would always tell us that Ole Hanson was a modern-day American hero.”

The bank’s own hardships spelled doom for the city, whose population plummeted. “San Clemente ‘Broke’; May Fire All City Employees” read an Oct. 19, 1935 headline in the Santa Ana Register. Bank of America owed San Clemente $125,000 in back taxes over six years. The council moved to eliminate all but five essential city functions until an eleventh-hour $2,500 deposit from the bank covered payroll and saved San Clemente.

Bank of America paid $100,000 in back taxes by year’s end and oversaw future development without regard to Hanson’s beloved Spanish Village ordinance. By 1936, the city council loosened it up for certain areas. “This charming senorita with the tomboy name, who has always clothed herself demurely in white, will now flaunt a little color in her outskirts,” reported the Santa Ana Register.

Evicted and exiled, Hanson lived his final days in Los Angeles. He continued in real estate while waging his last political battles, even finding one last “Red” to tangle with. Hanson teamed up with California Governor Frank Merriam in 1934 to defeat the incumbent’s surprise opponent, famed socialist author Upton Sinclair. He went on another barnstorming tour and created the Save Our State League.

60 years later, a group of Orange County residents would take the same name and affix it to what would become the anti-immigrant Proposition 187.

Hanson unsuccessfully ran for the U.S. Senate in 1938, the last gasp of his political career. On July 6, 1940, he died at home from heart disease at age 66. Newspapers more readily remembered him as Seattle’s fighting mayor rather than San Clemente’s founding father, even in OC. The Santa Ana Register recalled Hanson as someone who “broke a bitter strike in Seattle and boasted that thereby he had nipped a national revolution in the bud.”

A plaque honoring Hanson was unveiled at Casa Romantica in 2018 but his final resting place is at Inglewood Park Cemetery, 67 miles north of his most lasting achievement.

Ninety-five years later, Ole Hanson’s legacy looms over San Clemente like a marine layer, visible but thinning and dissipating over time.

The Beachcomber Inn, a hotel built after the Depression, hearkens to his fantasy heritage style. There remains, of course, enduring testaments to the city’s early days like the Abode, Casa Romantica and the Ole Hanson Beach Club.

By the 1980s, though, San Clemente feared losing its fantasy heritage aesthetic after decades of development free from it. The city responded by reviving Spanish Colonial Revival requirements for new and remodeled building in its downtown, North Beach and Pier Bowl districts. San Clemente’s redevelopment agency even rescued Casa Romantica from its derelict state in 1989, then eventually repurposed it as the cultural center it functions as today.

Newer developments, like the Outlets at San Clemente, conform to Hanson’s aesthetic. Nevertheless, homes, condominiums and apartments now dot the town in all different styles and shades. And those “perpetual” race restrictions advertised decades ago haven’t lived up to their promise; San Clemente’s Latino population hovers around 17 percent.

But the spirit of Hanson’s reactionary local and national politics remains alive in the city. Richard Nixon famously set up his Western White House here. And today, Hanson’s Americanism lives on in a new salesman turned politician.

“Make America Great Again” flags, a common sight in many neighborhoods, let the world know that San Clemente is still majority white and Republican. A month into coronavirus, residents betrayed their founder’s early pandemic wisdom in Seattle by protesting stay-at-home orders while waving those very same Trump flags in downtown. Last month, a pro-Trump rally drew hundreds of supporters, almost all without masks, brandishing signs that declared “Yes to Freedom! No to Socialism.”

And when a deputy’s fatal shooting of Kurt Andras Reinhold, a 43-year-old homeless Black man, led to a small Black Lives Matter protest this summer? San Clemente issued a curfew, and residents screeched on NextDoor about antifa threatening their town.

Hanson would’ve been proud.

Gabriel San Román is a native Anaheimer, former staff writer with OC Weekly, and the tallest Mexican in Orange County. Subscribe to his Slingshot! newsletter for weekly dispatches on the OC scene.